The Deloitte Global Boardroom Program recently released the results of its latest

The Board Frontier Topic survey, as published by Deloitte Global Boardroom Program, reveals that global business leaders understand the importance of and feel responsible for building trust within their organisations.

But despite this understanding, few participants in the survey categorised their organisation as achieving a high level of trust maturity, and around a third said they have no consistent approach to maintaining trust or only prioritise it in the wake of a crisis.

“For businesses, earning and protecting stakeholder trust is fundamental to ongoing viability and success, not just in terms of reputation, but as an important driver of financial performance,” says Michael Bondar, Deloitte global enterprise trust leader.

“When it comes to building trust, organisations should remember two key principles: every stakeholder counts – from shareholders to employees, customers, ecosystem partners and wider society – and action is key.”

Michael Bondar

“Trust is demonstrated by organisations performing with a high degree of competence coupled with positive intent,” he concluded.

Operationalising trust as a business priority

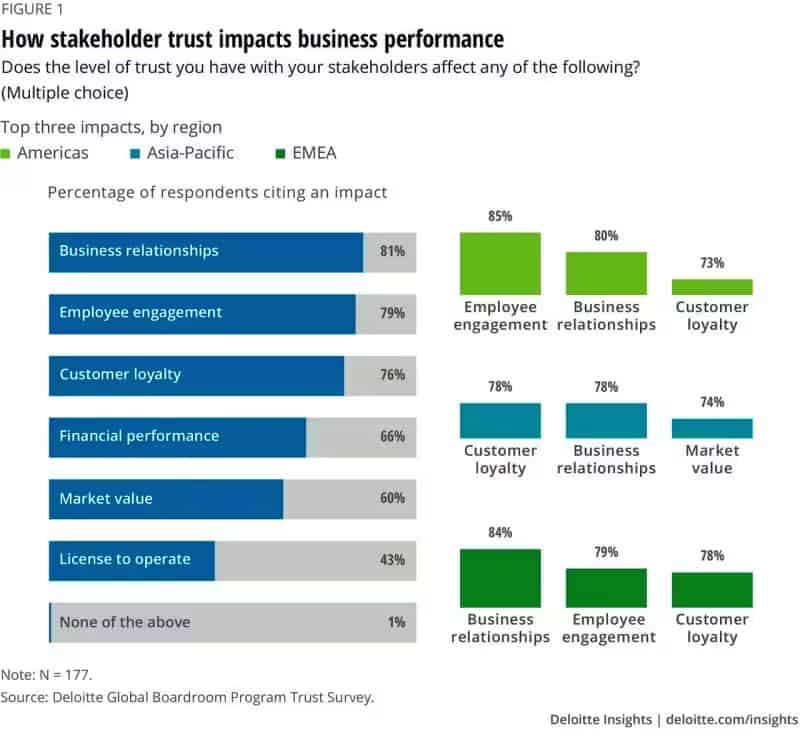

All respondents agreed that trust impacts performance: 94% said it’s “important” and only 6% said it’s “somewhat important” to their organisation’s performance. Respondents also noted that the level of trust their organisation has with stakeholders has a high impact on the following aspects of their operations: business relationships (81%); employee engagement (79%); customer loyalty (76%); financial performance (66%); and market value (60%).

However, just 39% of respondents categorised their organisation as achieving a high level of trust maturity, meaning they have well-defined trust objectives and metrics, take consistent actions across all parts of the organisation and regularly discuss trust in the board and executive meetings.

A greater number of respondents (45%) reported a moderate level of trust maturity, meaning that trust is acknowledged as a business imperative and discussed periodically at board and executive meetings, but has yet to be enacted formally throughout the organisation.

Sixteen per cent of respondents said their organisations have a low level of trust maturity, meaning they lack a solid definition for trust, leaders have occasional and reactive discussions, and they haven’t yet put processes in place for measuring or operationalising trust.

“Operationalising trust requires leaders to ensure that an organisation’s purpose is fully contextualised within its circumstances – including that of the broader industry, as well as its own access to the different levers that can make an impact,” says Seah Gek Choo, boardroom program leader, Deloitte Southeast Asia.

“This means that purpose must be defined both in broad and specific terms; organisations need to not only articulate clear values, but also define the specific behaviours that leaders, teams, and individuals can display to translate these values and build trust with stakeholders in their daily lives.” Seah Gek Choo

Owning the trust agenda

When assigning responsibility for managing the trust, respondents feel that both CEOs and boards have a leading role to play. Among 82% of respondents said the CEO is ultimately responsible for trust leadership at the company, while 95% believe the board should play a key part in building and protecting stakeholder trust.

Despite the broad acknowledgement of their responsibility, survey results suggest that boards have more work to do to embed trust as a prominent feature on the agenda. According to 53%, they have no fixed cadence for such discussions – being guided instead by events as they arise. Fewer than one-third (28%) of respondents said their boards put trust on the agenda twice a year or more, and 10% reported that they do not discuss trust at all as a board.

Seah explained that in the context of the role that boards can play, it is perhaps worthwhile also emphasising the important function of the Chair, which extends way beyond that of a board member.

“As they discharge their responsibilities, Chairs have an important role to play in embodying and conveying trust – for example, as they orchestrate the dynamics of multilateral exchanges between different board members, the board and other stakeholders, or management and outside expertise,” she continued.

She opined that it is not only a matter of managing diverse opinions and perspectives. “Building trust takes convergence – that is, landing on a common and fair outcome for their board members, management, external parties, and other stakeholders,” she elaborated

Influence of stakeholder

How an organisation responds to events can play an outsize role in determining the level of trust stakeholders place in that organisation. Crises call on corporations to address immediate challenges, but leaders also should look beyond the moment and make changes to policies and communications that support customers, communities, and the workforce.

Over the past 18 months, 67% of respondents said overcoming COVID-19 pandemic-related challenges was the main area of focus for building stakeholder trust. But as the pandemic becomes less of a pressing concern in many regions, Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues are quickly becoming some of the issues more likely to impact corporate trust building.

Deloitte’s survey shows this trend is accelerating: While 45% of respondents said ESG is a key driver of trust for their company right now, that number increases to 61% when respondents pointed to priorities over the next three years. They envision ESG and climate change becoming even more of a priority than other vital trust areas such as customer experience (52%), innovation (50%), and cybersecurity (49%).

According to Seah, boards in Southeast Asia recognise the importance of ESG considerations in securing their organisation’s social licence to operate. She further observed that of the three components – environmental (“E”), social (“S”), and governance (“G”), boards are most familiar and comfortable navigating dimensions relating to governance, with the environmental and social components being much less understood. “But this is not due to the lack of want of trying: boards in Southeast Asia take ESG issues very seriously; it has just been difficult for them to obtain a firm grasp of this new and emerging topic and find the right sustainability talent,” she concluded.