I delivered the opening keynote at a summit of high-tech supply chain executives. One of the topics we discussed was people and technology trends in operations. It was striking, but not entirely surprising, that the subtopic generating the most heat in the room wasn’t AI. It was everyone still grappling with how to manage return-to-office and hybrid-working expectations.

As the conversation progressed, it became apparent to me that we were having it through the lens of baby boomer and Gen X expectations — my own included. Except for the one millennial in the room, we were sitting in an echo chamber of leaders who, in the next decade, might very well be telling those pesky teenagers to get off our collective lawns.

The short version of the social story the group shared is that boomers and many Gen Xers spent most of their careers working in corporate offices and are generally happy to return to the familiar rhythms of prepandemic office life. Gen Zs are digitally connected and savvy. They more often prefer virtual working, but also desire “moments that matter” in the office, where they can immerse in corporate culture, see and be seen by managers and senior leaders and enjoy some of the in-office swag strewn by leaders desperate to have their people back on corporate soil.

Now, if only we could do something about those millennials.

Generation Y

“It’s your kids, Marty. Something’s gotta be done about your kids.” — Doc Brown, “Back to the Future”

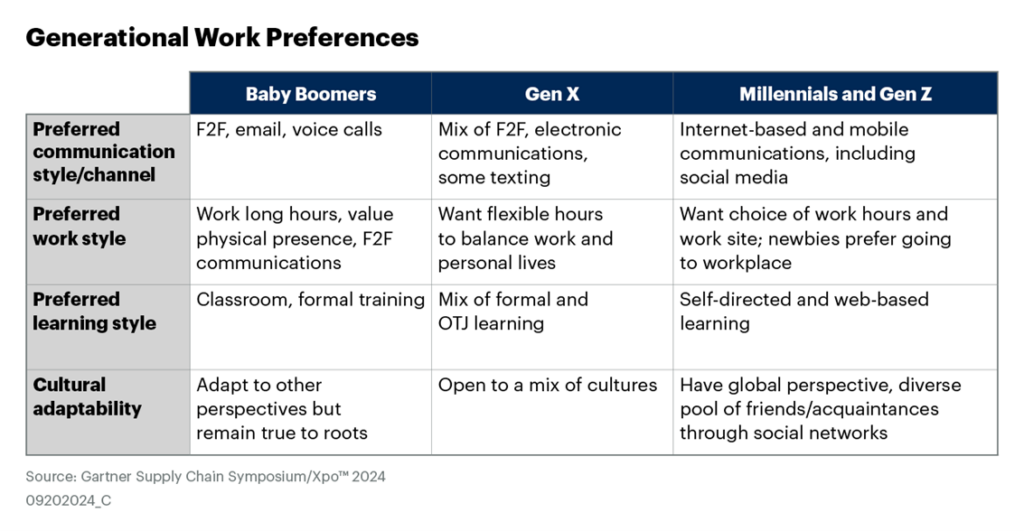

Let me start by saying that it is patently biased and unfair to lump people born over a 15-or-so-year period into monolithic groups with the same beliefs and characteristics. Disclaimer aside, there are recognisable trends in terms of communication, working and learning styles for the major generational groups currently employed by our companies.

Thinking back to the discussion in the room, those mostly older leaders viewed millennial employees as too often seeking schedule flexibility and accommodation to make family appointments, children’s extracurricular events, and so on. One leader raised a great point that even if one cohort is open to regularly meeting virtually at 8:00 p.m. to offset an afternoon away, that isn’t a fair ask of others who clocked their work during more standard hours in the office.

Flexible working

Other leaders piled on with perceptions of millennials as less motivated employees who can sometimes naively put purpose ahead of pragmatism. For a moment, I wondered why those entitled avocado toast lovers found “adulting” so difficult. But then the voices of my Gen Z kids entered my mind: “Dad, don’t be cringe.”

All kidding aside, it can be easy to fall prey to a cycle of unrealistic expectations and judgments. Call it “The Second Year Effect,” where a group is treated badly as first-year students and then perpetuates that poor treatment in the next class. Since the first group ultimately lived through the fire, the justification for their behavior is that it builds character in the face of adversity.

Here's another perspective. At least in the United States, Gen X was the last generation to regularly have their parents kick them out of the house with the simple requirement of being home before the streetlights came on. Conversely, millennials are the first cohort where kids playing unsupervised in public might prompt a call from the authorities for child endangerment. Putting the pieces together, we’ve raised expectations on the amount of time and involvement required to raise children while generally holding work expectations steady.

Adjusting perspectives

We have a collective opportunity to rethink how we support any generation raising young children while sometimes caring for aging parents. In many ways, raising a family in today’s world is harder. Inflation and unequal wealth distribution have made it more expensive for many to afford shelter and food. Social media has our kids (and us) addicted to their screens and living in a fishbowl of judgment, which has led to skyrocketing levels of anxiety and depression.

Now, here’s the kicker. Consider that in most developed nations, the population is in decline. There have been numerous reports about governments desperately trying to incentivise young people to start families, but nothing seems to move the needle. Beyond financial incentives, perhaps, as a broader society, we need to adjust our perspective on work flexibility to create an environment where young people feel they have the space to raise families.

Originally posted in Gartner